The File Drawer

Farage's Brexit Party Announcement and the 2019 Campaign

John Curtice, Stephen Fisher, and Patrick English made headlines recently for claiming that Nigel Farage’s decision to stand down his party in certain seats saved the Labour Party from an even worse result in the 2019 general election. They have a nice blog on the topic that they released on Elections Etc. today. I also have some data on this topic, but haven’t released it until now.

In the middle of the 2019 campaign there was an ONS announcement of the latest GDP data. At that point, the previous quarter’s GDP had been negative and there was a real chance that the next quarter might be negative too. If that were the case, it would imply that the country was in recession in the middle of the campaign. I wanted to know if and how quickly voters would respond to the news, so ran a survey of around 18,000 people with YouGov over the course of several days that straddled the announcement date.

I had wanted to use these data to run a regression discontinuity design to estimate the effect that the economic announcement had on voters’ economic perceptions. Unfortunately for me, but fortunately for the rest of you, two things happened that ruined my data collection. First, the GDP announcement was positive. Second, Nigel Farage intervened and announced on the same day that his Brexit Party would stand down candidates in 317 Conservative-held seats.

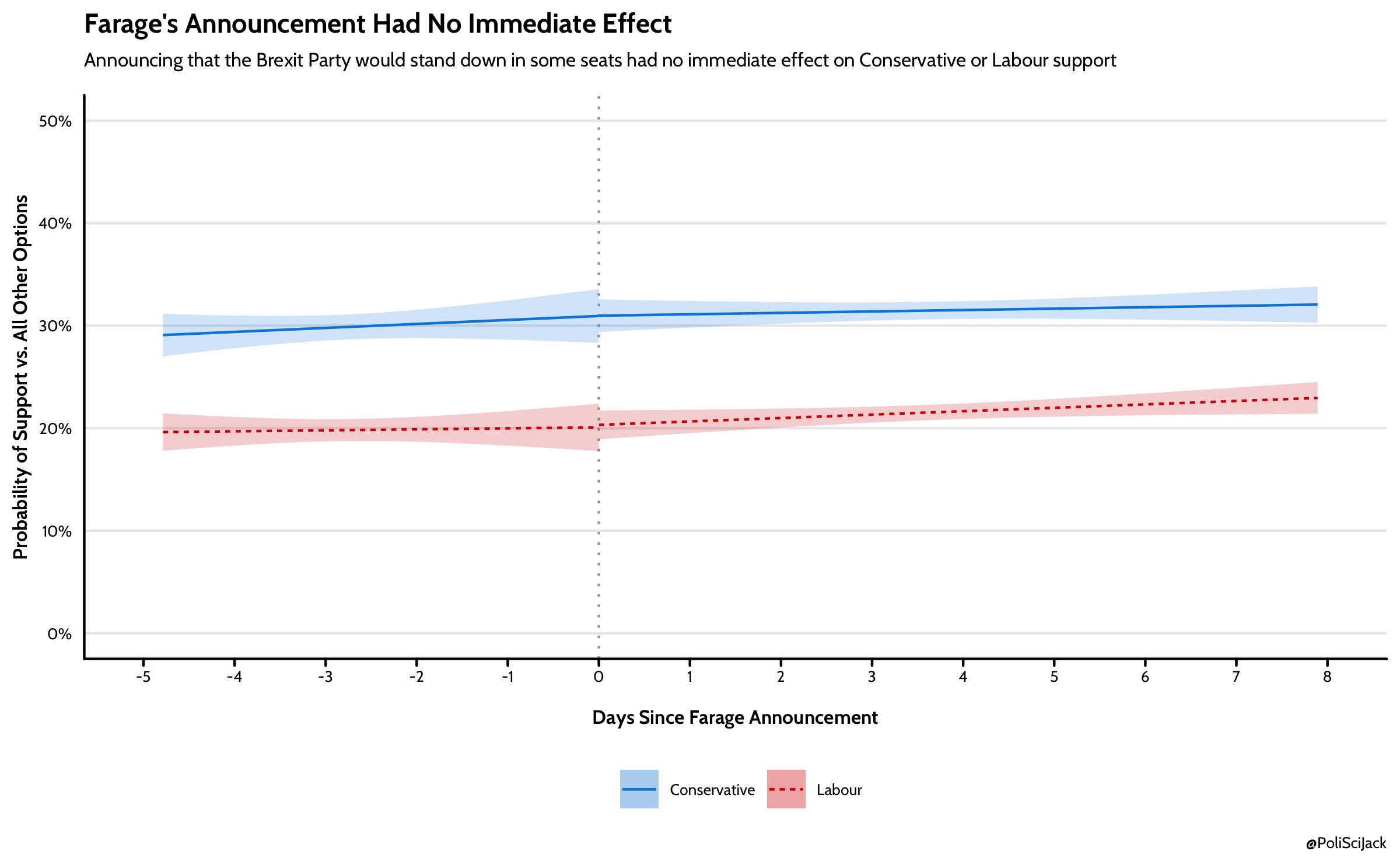

I decided to change tack and see how Farage’s shock announcement affected how people intended to vote during the campaign. Turns out, it didn’t. The figure below is a simple RDD that shows how Conservative and Labour voting intention changed over the course of the days included in my survey. (A less simple non-linear RDD produces almost exactly the same results). As we can see, the vote share for both parties goes up over time, but there isn’t really a change around the announcement date itself. Note that I haven’t excluded people who said that they wouldn’t vote etc. to ensure that the implied denominator is consistent regardless of treatment status. This is why the vote shares here are a little lower than we might otherwise expect.

This implies that the effects that John, Steve, and Patrick find didn’t affect the parties that voters supported during the campaign. Rather, it likely affected how they voted by constraining voters’ choices sets in certain constituencies.

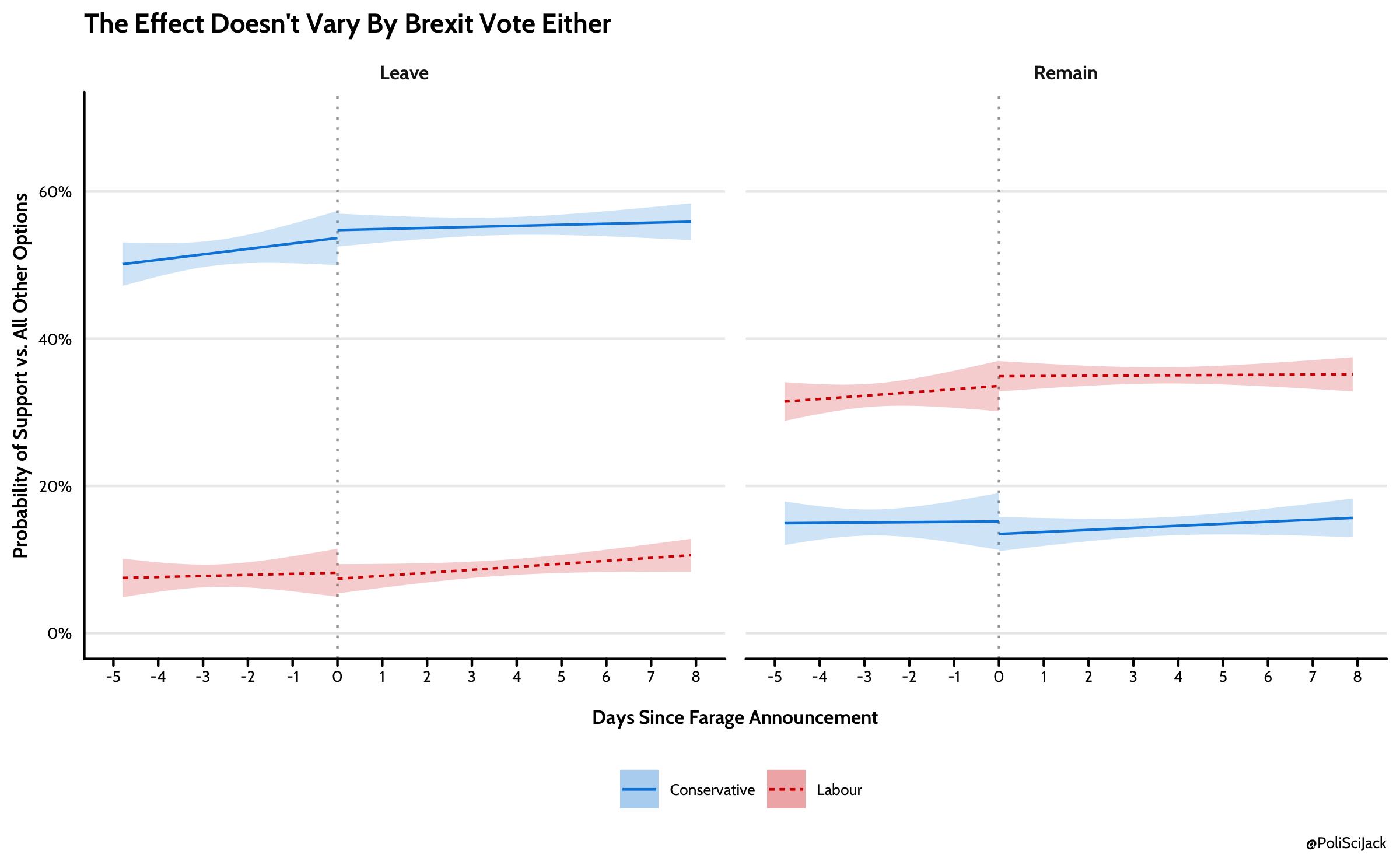

One might think “Yes, but perhaps this is because Leave and Remain voters moved in opposite directions, cancelling on aggregate”. And if you did, you’d be sensible but wrong. As the figure below shows, there was no discernible effect when we break things down by vote in the 2016 referendum either.

Overall, I think these null findings are interesting for two reasons. First, they help us to narrow down how Farage’s announcement might have led to the results that John, Steve, and Patrick find. Second, they go to show that seemingly important events that occur during election campaigns can still not affect support for different parties.

If anyone’s interested in doing something with this data set, I’m more than happy to share it. They include standard voting variables plus some retrospective personal and national economic perception items. Likewise, similar data are available in the British Election Study Internet Panel.